Ann Ming’s Story Offers Hope to All Authors

By Andrew Crofts

I have ghostwritten for many amazing people over the last forty or more years; people who have shown extraordinary bravery and persistence in the most challenging situations life can throw at us; surviving childhood abuse, genocide, slavery, extreme poverty, enforced marriage – and so the list goes on. Some of the resulting books have been rewarded with bestseller status, others have totally failed to find the readerships I believed they deserved.

In 2007, Ann Ming and I sat down together to tell her amazing story in book form.

Not only had Ann lost a beloved daughter to murder, she had been the one to find the victim’s body, in the most gruesome of circumstances. She then went on to battle with the most powerful people in the country, in order to ensure that her daughter’s killer was convicted, changing the 800-year-old law of double jeopardy in the process. It was a story of astonishing heroism and grit.

The resulting book was called “For the Love of Julie”, and it was well received when it was published the following year. On Amazon it has well over a thousand five-star reviews. But then it petered out, as the majority of books do – until now.

Eighteen years after we first sat down, the media is full of interviews with Ann, who is now close to eighty years old, and full of praise for the performance of Sheridan Smith, the actress who is portraying her in a televised adaptation, entitled “I Fought the Law”. Sheridan, and others, have been quoted repeatedly as saying they can’t believe they had never heard the story before, or that Ann’s name is not known to everyone.

And therein lies one of the most frustrating elements of the book publishing universe. You can come across an extraordinary story about an extraordinary person. You can write a book which readers praise to the skies and shower with stars, yet still it takes a television adaptation to get that story in front of millions of viewers, rather than just a few thousand readers.

It took eighteen years for that to happen to Ann’s story, and if the screenwriter, Jamie Crichton, had not happened to stumble upon it, and decide to champion it to a production company, it probably wouldn’t have happened at all.

But although this illustrates one of the frustrations of book publishing, it also offers hope to all struggling authors. Once your book is out there, particularly in these days of Amazon and the Internet, you never know when its turn in the spotlight may come. Every day could be the day that you get a call from a television or film company, to say that they want to launch your story into a whole new stratosphere of success.

As she is being garlanded with praise, after waiting patiently for so long, Ann Ming is, once again, an inspiration to us all.

50 Years of Being a Full-time Freelance Writer

Andrew Crofts

I have been earning a full-time living as a freelance writer for fifty years. There have been ups and there have been downs. The “ups” have included the month where two of my books received advances of £300K each, and the month where I had four books in the Sunday Times bestseller list simultaneously. There was also the book which eventually sold something north of five million copies, and the client who wanted to meet on his private island in Bermuda. There have been books ghostwritten for heads of state and bonded labourers, refugees, genocide survivors and child brides, pop stars, soap stars, reality tv winners, hairdressers, and Basil Brush.

These “ups” are the jewels of memory that sparkle amidst the decades of typing, submitting and waiting for industry gatekeepers to get back to me, and all the manuscripts which were rejected by every agent I could find, let alone every publisher. Then there were the editors who “loved” the books but wanted them totally rewritten, and the books that were published but sold not a single copy – a sort of slow death by rejection. There were the publicists who cheerfully gave up trying to get media coverage after a week, editors who changed employers half way through the editing process, or fell pregnant, or died. There were the legal departments who covered pristine manuscripts with their scribbled worries, and there were the reams and reams of unintelligible royalty statements that have been landing on the doorstep every few months, telling me I still owed the publishers thousands of pounds.

The end result of these first fifty years? I have published over a hundred books and managed to support a family and raise four children. If I’d possessed a crystal ball fifty years ago, would I have embarked on the same life journey? Absolutely.

When my journey started, in 1970, my manuscripts were bashed out on a pre-war, upright typewriter, and dispatched by post, with self-addressed envelopes, direct to publishers, (after lengthy searches for the right addresses). After months of heady dreaming, the now tattered envelopes would arrive back, accompanied by dream-crushing rejection notes. I doubt that process had changed much over the previous hundred years. But I was seventeen and optimistic. I had written my first novel, (when I was meant to be paying more attention to my exams), and I was moving to the bright lights of “swinging” London, to share a flat in Earls Court with a dozen or so people, all of us quite certain we would be rich and famous very soon indeed.

It would take five years of hard typing and draconian budgeting, trying out every avenue of freelancing, before I was selling anything I had written, and ten years before I had managed to carve a small niche as a travel writer. In between hammering out more submissions to publishers, I was then able to visit exotic places I would otherwise not have got to, meeting exotic people I would otherwise never have had access to, providing more for me to write about in my fiction.

By 1990, twenty years after setting out, I was actually making it in through the doors of agents and publishers in my search for people who would fund publication of my work, since I could not afford to fund it myself. One of the books I wrote was “Sold”, the story of Zana Muhsen, which would, over the following few years, sell in many countries, one year becoming France’s bestselling non-fiction title.

By the time the Millenium ended, my income was steady and technology was starting to streamline the lives of all writers. Word-processing was doing away with the need for endless drafts and messy struggles with carbon paper and Tippex, and the gradual adoption of email was turning self-addressed envelopes, and frustrating queues at the post office, into unmourned memories.

Amazon was opening up new ways for writers to reach wider audiences. The gatekeepers within the agencies and publishers remained trapped inside the culture of waiting – it does, after all, still take a lot of time to read a manuscript – but writers could now circumnavigate these waiting rooms from hell, and even cut down on the levels of rejection they had to face.

So today the main challenge is proliferation. Because it has become easier to produce manuscripts, there are far more of them out there, competing for everyone’s time, and AI is destined to magnify that problem a millionfold.

But writers also now have the services of creative agencies and bespoke publishers to call upon. Coming to Whitefox, for instance, feels, to this world-weary traveler, like being ushered left as I walk onto a long-haul flight, after decompressing in a comfortable airport lounge, insulated from the anxiety-inducing queues and jostling crowds.

Writers no longer have to sign away their copyright, which means that they can keep any money generated by their work, not just a tiny percentage of it. We can maintain ultimate creative and financial control, while at the same time receiving advice from all the same experts who work for the traditional publishing houses. Above all, however, just as when you turn left on a plane, or visit a private consultant with an ailment that is worrying you, you encounter people who will take the time to be as supportive and helpful as possible.

As with the airlines and the doctors, of course, there is an upfront cost for these services, and there is always a risk that you will not earn enough to cover those costs. But as anyone who has ever stretched out flat on a bed during a long-haul flight knows, it is sometimes worth investing if it avoids having to spend twelve hours crowded into the back of a plane with your knees under your chin, sleeplessly waiting for the ordeal to end, while being ignored by the overworked cabin crew.

Bestselling Ghostwriter Reveals the Secret World of the Author for Hire

Robert McCrum in The Observer

Andrew Crofts has written 80 titles and sold some 10 million copies in a 40-year career, mostly under names far more famous than his own – until now – Robert McCrum

Crofts: ‘You get the commission, have the adventure – anywhere from a palace to a brothel – and return to the security of your own home.’ Photograph: David Woolfall

“Behind the title of ghostwriter, I could converse with kings and billionaires as easily as whores and the homeless, go backstage with rock stars and actors. I could stick my nose into everyone else’s business and ask all the impertinent questions I wanted to. At the same time, I could also live the pleasant life of a writer… ”

Next week, in an exceedingly rare departure from a lifetime of tight-lipped professional discretion, Andrew Crofts, one of Britain’s most invisible and yet successful writers, a bestseller you will never have heard of, will step out of the shadows and lift the veil on a trade that’s almost as old as that other ancient calling. With a bit of skirt-lifting, and more than a hint of saucy revelations, Confessions of a Ghostwriter will be a timely publication.

There’s an old saying that you should never judge a book by its cover. Today, perhaps, that conventional wisdom has rarely had more meaning. To a degree that might astonish the reading public, a significant percentage of any current bestseller list will not have been written by the authors whose names appear on the jackets.

Among the many mysteries of the British book world, none is quite so opaque as the life of the ghostwriter, the invisible man or woman who fulfils the vanity of those who want their name on the cover of a book but who, for the life of them, cannot write.

You may not know it, but literary ghosts are everywhere. In this golden age of reading, publishers desperate for copper-bottomed commercial titles in bestselling genres – misery memoir, sporting lives and celebrity autobiography – will not hesitate to sign up surrogate authors.

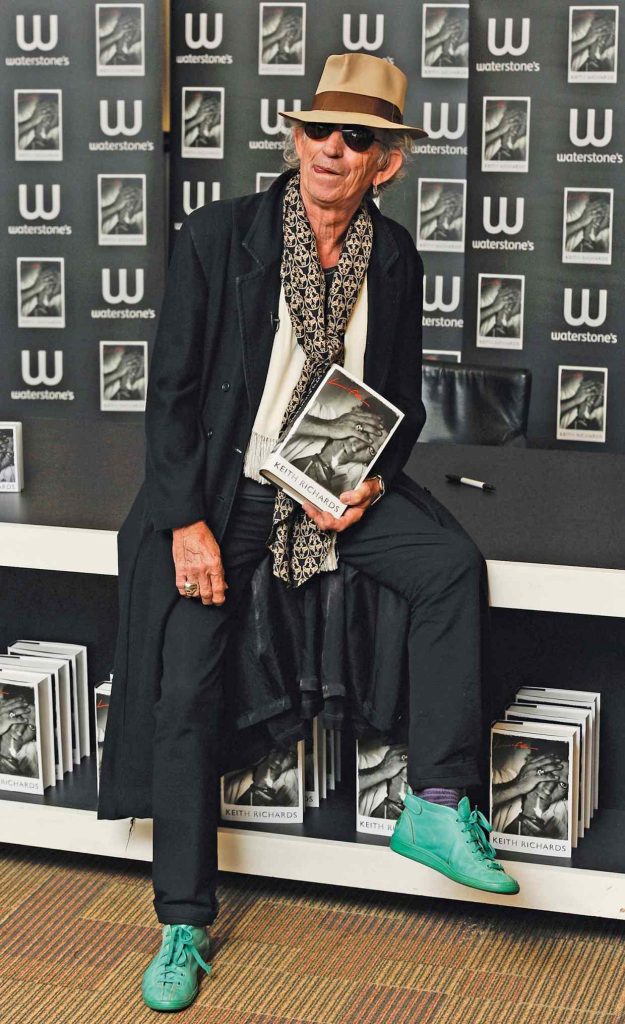

Behind such brand names as Sir Alex Ferguson, Jordan, Andy McNab and Victoria Beckham lurks the shy figure of the ghost. Sometimes, there is no deception. Keith Richards’s Life was written by James Fox. Katie Price (aka Jordan) boasts that she does not do her own typing, and relied on Rebecca Farnworth to launch her career as a novelist with Angel. Further down the food chain, even the infuriating meerkat from the comparethemarket.com adverts has had A Simples Life put together by Val Hudson, formerly of Headline books.

The top category of ghosted titles remains the misery memoir, books such as Tell Me Why, Mummy or Please, Daddy, No, or Sharon Osbourne’s Extreme: My Autobiography. At its peak, this genre accounted for almost 10% of the UK book market, closely followed by celebrity autobiographies (Russell Brand’s My Booky Wook), true-crime memoirs (Dave Courtney’s Stop the Ride, I Want to Get Off), sporting lives (Wayne Rooney’s My Story So Far) and tales of derring-do (Bruce Parry, Bear Grylls, et al).

Ghostwriting in the English-speaking world is big business. The term was coined by an American, Christy Walsh, who set up the Christy Walsh Syndicate in 1921 to exploit the literary output of America’s sporting heroes. Walsh not only commissioned his ghosts, he imposed a strict code of conduct on their pallid lives. Rule one: “Don’t insult the intelligence of the public by claiming these men write their own stuff.”

Walsh’s code lingers. The acknowledgments page of many ghosted books will thank partners, children, even family pets, before making a discreet, sometimes grudging, nod to the invisible man or woman who quarried the angel from the marble. Alternatively, and more transparently, the book will be credited “as told to”, or “written with”, or “edited by”

Those innocuous phrases often mask a world of private pain: tearful interviews, angry confrontations, threats of violence, shocking revelations and interminable waiting, waiting, waiting. In France, ghosts are known asnègres, and there is a kind of slavery implicit in this transaction. The ghost’s world may be one of jeopardy, but it’s probably less perilous than it is depicted in Robert Harris’s thriller The Ghost, a book credited by many with outing the ghost’s tradecraft.

As with any book, the struggles of the ghosted book are all to do with love and money. First, there’s the inevitable contract tussle. Traditionally, the ghost receives 33% of the advance (plus royalties). In recession, this has been squeezed to as little as 10%, a figure the better class of ghost will disdain.

Often, battles over the money pale into insignificance next to the titanic clash of egos involved in taking on another’s voice and character. Some ghosts, who generally speak on conditions of anonymity, report that the subject they approach with utter dread is the fragile personality with pretensions to authorship.

Who, after all, is not vulnerable to the tug of amour-propre? The ghost, who starts out as a hybrid of therapist, muse and friend, enters a psychological minefield. Accordingly, the ghost is advised never to forget that, at the end of the day, he or she ranks somewhere between a valet and a cleaner.

I recall, some years ago, a female pop star attending a book trade prize-giving for which her ghosted bestselling memoir had been shortlisted. Before this honour, she boasted she hadn’t even opened, still less actually read, the book that bore her name. When she duly won, she left her ghost at the table and graciously collected her prize, all smiles, modesty and gratitude, the model author. When she returned to her publisher’s table, the woman who had actually written the book reached out, instinctively, to touch the trophy. Bad move. The star snatched it back, clouting her ghost across the cheek to remind her who was boss. When you pay the piper, you call the tune.

Crofts has written some 80 books, sold more than 10m copies and appeared a dozen times in UK bestseller lists. In a rare interview with the Observer, Crofts described some 40 years of ghosting. An easy going, youthful man in his early 60s, Crofts was educated at Lancing College, but says he was “too arrogant” for university, and stumbled into ghostwriting because, he says, “I didn’t want to have a permanent job”.

Ghosts, notes Crofts, lead episodic lives: “It’s a perfect arrangement. You get the commission, have the adventure – anywhere from a palace to a brothel – and return to the security of your own home.” Crofts is a child of the 1960s who seems to have transformed a secret vagrancy into a way of life. At 17, on leaving school, he nurtured vague literary ambitions, wrote a novel (“more Robert Harris than Virginia Woolf”), suffered the inevitable rejection and began writing PR copy. With typical English self-deprecation, he describes himself as “an opportunistic hack” who would “do anything I got paid for”. When pressed, however, he admits to taking pride in his craftsmanship and in having made “a good living as a writer for 40 years”.

When he started, he recalls, “‘ghostwriting’ was a dirty word”. In 1984, with the chutzpah of youth, he launched himself in business. His approach was simple and direct. He placed a three-word ad – “Ghostwriter for hire” – in The Bookseller, and waited for the phone to ring.

Crofts was lucky, with impeccable timing. Book publishing would be turned inside out by the IT revolution. Ghostwriting, similarly, was transformed by the web. “The internet made all the difference”, says Crofts, who was one of the first ghosts to launch his own website. Now, he gets three or four approaches a day. “I’m writing all the time,” he says.

Under his own name, and from a certain pride in his trade, he went on to publish Ghostwriting, a how-to manual. When Robert Harris read this as part of his research for The Ghost, he sought permission to quote some of Crofts’sobiter dicta (“Of all the advantages that ghosting offers, one of the greatest must be the opportunity to meet people of interest”) as chapter-heads. The Ghost, says Crofts, was “a gift from the gods. Harris did us all a huge favour.”

Since 2007, Crofts has become the ghost’s ghost, the go-to spook in a now-booming market. “I charge a lot,” he admits, and concedes that his fees average six figures. Crofts, who currently earns more than most professional UK writers, is sought after by overseas celebrities, politicians and stars, especially in India. He also works with Russians, Africans, Arabs, and South Americans. “Everyone loves London,” he says. “This is soft power in action. London is seen as the home of publishing, a place that’s kosher, where Dickens walked the streets.”

His rule for accepting a new client is that they must have a good backstory. He took on Alexandra Burke (of The X-Factor) because of her mother’s career sacrifice. “She was in hospital watching her daughter on TV, living her life,” he says, and confides a special interest in tales of childhood abuse. Sold, the shocking rape story of Zana Muhsen, has shifted 5m copies and, Crofts believes, created a new market for books such as Jane Elliott’s The Little Prisoner. Crofts also took on Big Brother‘s Pete Bennett, an acute Tourette’s sufferer, out of respect for “an extraordinarily attractive character”, and ghosted Pete: My Story, another bestseller.

Is there anything he wouldn’t do? “I have to be interested”, he says, conceding that he could happily coexist with monsters. “I have a horrible feeling that if I’d got the call from Germany in the 1930s I would have hopped on that plane like a Mitford.”

Fantastic ghostwriters and where to find them

Horatia Harrod, Financial Times

For CEOs and sports stars, rock legends and politicians, hiring a ghostwriter is the ultimate public relations exercise. Horatia Harrod talks to top ghostwriters about the unwritten rules of this shadowy literary underworld.

A few years ago, Andrew Crofts went to a grand party in Dubai. Although his hosts had flown him out specially for the lavish two-day affair, putting him up at one of the city’s seven-star hotels, he was not an honoured guest. Indeed, this affable, bespectacled 64-year-old was not a guest at all: he was, in fact, a birthday present, a gift from the children of a billionaire patriarch to their ageing father.

Crofts, you see, is a ghostwriter. For more than two decades, he has been the faithful amanuensis to a host of authors, privy to the intimate confidences of politicians, princesses, soldiers, CEOs and spiritual leaders. Crofts charges from £100,000 to £150,000 for his services, taking three to six months to write each book. “I would say, think of this as like hiring a really expensive artist to do a really nice portrait,” he says, sipping black coffee in the living room of his rambling Sussex home. “It’s a lovely thing to do, I promise you’ll enjoy the process, you’ll love the final product, but it’s going to cost you a lot of money.”

Of the hundred or so books Crofts has co-written, perhaps a quarter credit him on the cover, another quarter mention him prominently in the acknowledgements, but half offer no clue whatsoever as to his involvement. Yet, despite his discretion, Crofts has attained a paradoxical measure of fame. When Robert Harris wrote his novel, The Ghost – later a Roman Polanski film starring Pierce Brosnan and Ewan MacGregor – every chapter began with a quote from Crofts. The first ran: “Of all the advantages ghosting offers, one of the greatest must be the opportunity that you get to meet people of interest”.

James Fox said trying to pin down Keith Richards for his memoir, Life, was like trying to catch a wily salmon

“You have a passport into other people’s lives as a trusted confidant,” says Crofts. “A lot say afterwards, ‘That was like therapy’. A ghost is probably the least judgemental person they’re going to come across, because even a therapist is looking for angles. But a ghost just keeps asking questions: ‘How does that feel?’ ‘What happened next?’ I would imagine it is very pleasant.” Crofts says he gets two or three enquiries every day from people thinking of engaging him as their ghost. When he first branched into this line of work after many years as a freelance writer, he put an advertisement for his services in The Bookseller, the trade magazine for the publishing industry. Today, most people contact him via email, having found him online – if you type “hire ghostwriter” into Google, his is one of the first sites to pop up.

There is a somewhat furtive air to these early exchanges, before contracts have been signed and trust established. “I remember some years ago having breakfast when the phone rang,” says Crofts. “This distant voice said, ‘Do you like Kuala Lumpur?’ I thought, ‘I don’t know, I’m eating a boiled egg.’” The voice on the end of the line turned out to be the personal assistant of Loy Hean Heong, a Malaysian billionaire who did ultimately employ Crofts to write his memoir. “He was very conscious of image,” says Crofts. “When we got to Kuala Lumpur, he wouldn’t invite me to his house until they’d finished the goldfish pond – which was like something from the gardens at Versailles.”

The nature of his business is such that he remains generally tight-lipped about the identities of his subjects. It is easier to name the ones who got away: Imelda Marcos, with whom he shared a stilted lunch in the Philippines, or Suzanne Mubarak, wife of the former Egyptian president, who was on the verge of hiring Crofts just weeks before her husband was deposed in the Arab Spring. When deciding whether to take on someone’s story, Crofts arranges a preliminary meeting, and is then guided by his interest. “If I’m interested enough to want to ask questions in the initial approach, when they first ring or email, then I can probably find enough for a book,” he says. Moral questions about a person’s life rarely trouble him – in that regard, Crofts likens himself to a lawyer. “I think one of the skills a ghost needs to have is to be completely non-confrontational,” he says. “You listen to their story and then you help them to plead it.”

Crofts is part of his peculiar profession’s elite. According to Dan Gerstein, founder of Gotham Ghostwriters, you get what you pay for. Gerstein founded his New York-based agency nine years ago to help would-be authors negotiate this little-understood business, and has built up a stable of some 1,900 ghosts, many of whom are high-profile authors in their own right. “Because it’s such an opaque market it’s totally un-standardised,” says Gerstein. “But to give a crude segmentation, there’s a low end, the $25,000-$40,000 range, to write a short business book or a very basic memoir. Then there’s the mid-range, anywhere from $75,000 to $125,000, where you’re getting a serious, qualified writer to produce a book that will enhance your reputation. And then there’s a whole other class of book from the low hundred thousands up to $300,000, where the principal tends to be a very high-profile figure and the ghost has written multiple bestsellers.”

Among that rarefied group is the American author William Novak. In the early 1980s, Novak became the ghost to Lee Iacocca, one time-president of the Ford Motor Company who went on to save Chrysler from bankruptcy. His memoir, Iacocca, sold more than 2.7 million copies worldwide, and helped make respectable the idea that even great business minds might need help bringing their thoughts to the page.

It was in many ways an unlikely match. Novak was in his early 30s, and the books he’d already written under his own name – a study of marijuana culture, a compendium of Jewish humour, a look at The Great American Man Shortage – had enjoyed only moderate success. Of business he knew “nothing”, although he had cultivated an amateur interest in the stock market. “I had a friend who was a junior editor at Bantam Books, and she mistakenly thought that somebody with an interest in the stock market must know a lot about business,” says Novak, speaking from his house on Cape Cod bay. “You know, in the land of the blind, the one-eyed man is king. She said, ‘Would you be interested in helping a famous businessman write his memoirs – only I can’t tell you who it is.’ I was sure the businessman was Armand Hammer [one-time head of Occidental Petroleum], who was the only one I could name. Of course, it turned out to be Lee Iacocca, who I’d barely heard of.”

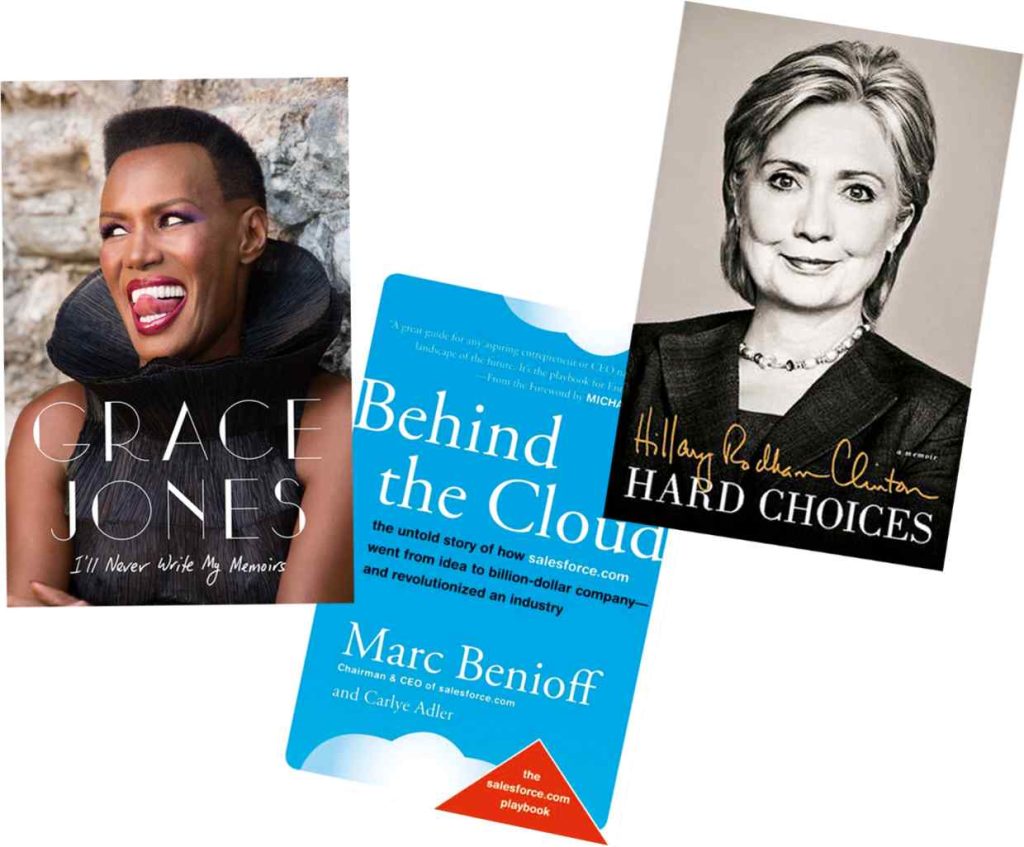

From left: It took Paul Morley two years to produce Grace Jones’s I’ll Never Write My Memoirs. Carlye Adler is a favoured ghost for Silicon Valley entrepreneurs such as Marc Benioff. Hillary Clinton made sure she credited her “book team” for her 2014 Hard Choices

Novak accepted a fee of $45,000 to ghost Iacocca’s book. He thought the project would only take a year to complete; in the end it took twice as long. “It was embarrassing to be number one on the American bestseller list for almost two years, because I was sure everybody thought I must be terribly wealthy,” he says. “They didn’t know I wasn’t getting any share of the royalties or the international sales.” There is no standard contract for ghosts and their principals, although almost all ghosts will expect to be paid upfront. And today, Novak prices himself high.

After the grand success of Iacocca, Novak began to be approached by other powerful people who wished to share their stories. He turned down the chance to ghost for Nelson Mandela – “I didn’t want to spend months away from home” – and Ronald Reagan, although he did ghost Nancy Reagan’s 1989 memoir, My Turn. “It was the most difficult project I ever did,” says Novak. “She had what is a very nice quality in a friend – she’d rather listen than talk. But that’s my job!”

What surprised him the most about the process was the lack of intimacy. “I thought I would probably have to live in Iacocca’s house and become his son,” says Novak. “I never even saw his house. We were not close at all. And yet, that didn’t matter. What matters is how good a talker a person is, and what the writer is able to do with that talking.” Novak was struck by how little his subjects revealed beyond what they needed to. The ghost can probe and publishers can make demands, but ultimately control rests exclusively with the author. “With Iacocca, I remember saying, ‘Lee, we’ve got to talk about your mistakes as well as your successes.’ He said, ‘I can’t think of any.’”

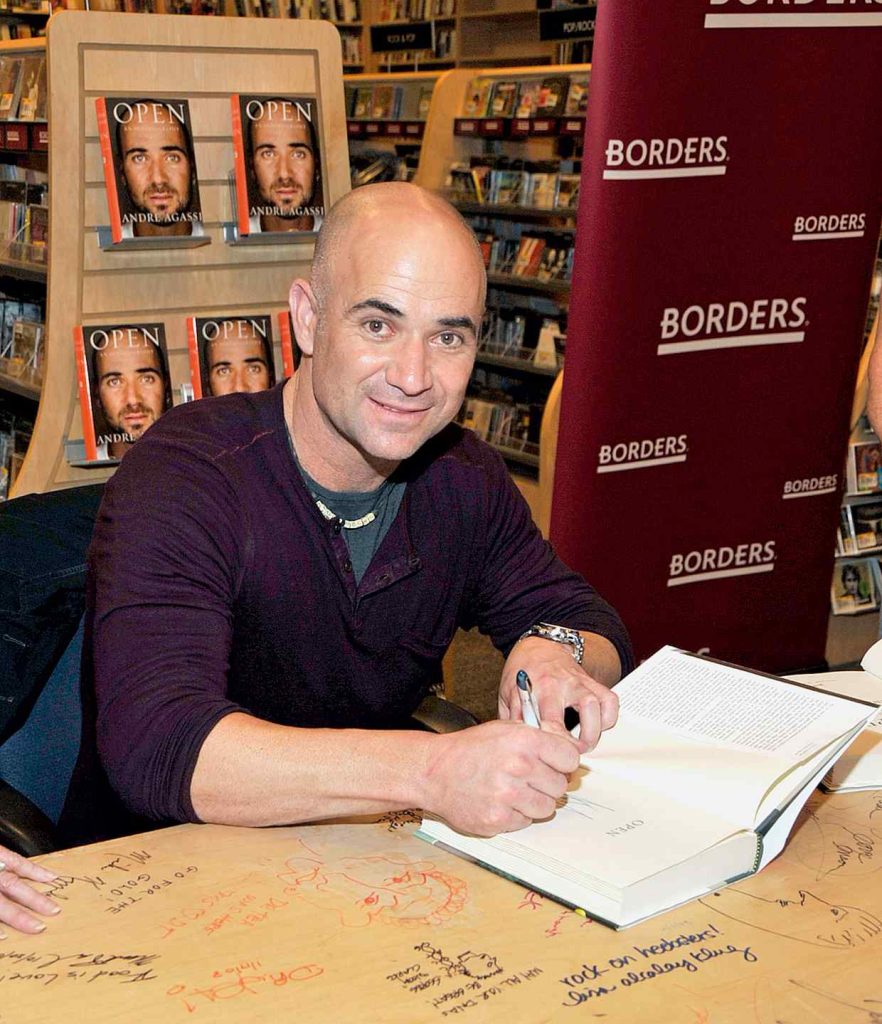

Andre Agassi did 250 hours of interviews for his memoir, Open

While contracts and non-disclosure agreements offer a measure of further protection to high-profile subjects, they are rarely airtight. There are many cautionary tales of ghosts who have broken cover to criticise the people they’ve worked with. The most recent example of this is Tony Schwartz, co-writer of Donald Trump’s The Art of the Deal, who offered a very disobliging picture of his former boss to The New Yorker in the run-up to the US election. Hillary Clinton, meanwhile, was accused by Barbara Feinman Todd, ghost of her 1996 bestseller It Takes a Village, of failing to give her a promised credit in the book’s acknowledgements. (She didn’t make the same mistake in her 2014 book Hard Choices, where she credited her “book team” of Dan Schwerin, Ethan Gelber and Ted Widmer). Dan Gerstein says that most ghostwriters take the promise of confidentiality very seriously. “But,” he adds, “the best thing to do to instil loyalty is not to command it but to earn it.” Among other revelations in Tony Schwartz’s mea culpa was the fact that Trump did not have the patience to conduct sit-down interviews, so he had to make do with shadowing and eavesdropping on his conversations for 18 months.

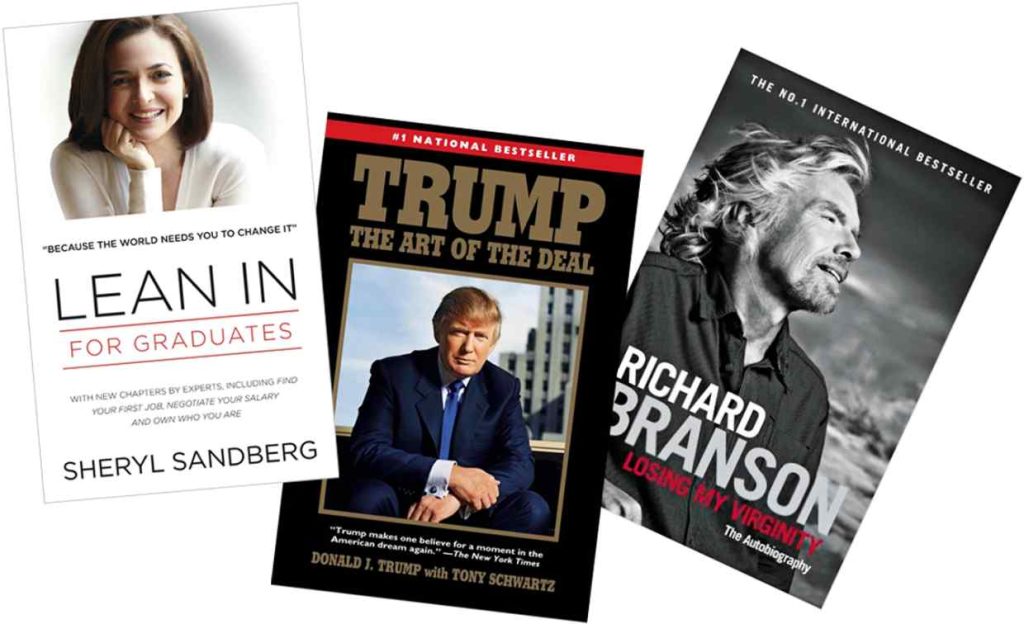

Jay Moehringer, who ghosted Andre Agassi’s 2009 memoir, Open, worked from 250 hours of interviews with the tennis player. James Fox spent five years trying to get the material for Keith Richards’ memoir, Life – he likened his attempts to pin down the guitarist to the pursuit of a wily salmon. Edward Whitley took two years helping to shape Richard Branson’s autobiography, Losing My Virginity, as did Paul Morley on Grace Jones’s I’ll Never Write My Memoirs; while the journalist and comedian Nell Scovell worked with Sheryl Sandberg to produce Lean In within a year.

Andrew Crofts, meanwhile, says he can produce a first draft based on a weekend’s worth of conversations. There are no real rules as to the time commitment for which a would-be author should be prepared. “How much time do they personally have to give me?” says Novak. “As much as possible. With Iacocca, I had the least time, but he was a very efficient talker, and I had access to everything he’d ever said in print. I know a guy who writes five books a year. Just one of mine took five years.”

Neil Scovell produced Sheryl Sandberg’s Lean In within a year. Tony Schwartz criticised Trump after ghosting The Art of the Deal for him. Edward Whitley took two years to shape Richard Branson’s Losing My Virginity

Carlye Adler, a favoured ghost for Silicon Valley entrepreneurs such as Marc Benioff and Maynard Webb, says that she usually envisages spending eight to nine months per book. “A lot depends on how much research is involved, the availability of the author and/or participants, and determining the best time to launch the book,” she says. “Books are ‘crashed’ [done at high speed] all the time because it becomes imperative to have it out for a certain event or circumstance. That’s not always best for the writing process, but it might be best for the book.”

According to Dan Gerstein, the first question any prospective author should ask is: “Why am I writing this?” “Some clients want to write a New York Times bestseller, in which case they’ll need someone to write a dynamite proposal for a traditional publisher. If you’re a tech CEO or entrepreneur, and you want to get your book out fast, on your terms, you should consider self-publishing. Whatever the method, a book creates a badge of credibility that’s unequalled in any other medium.”

It may be that an author does not wish ever to publish their book. This is about the most elite class of all: those who can afford to engage a writer of the calibre of William Novak to produce a book that will never be sold anywhere. When Novak first heard of this practice, he was stunned. “I had never heard of such a thing,” he says. “It turns out there are many books like this, but they’re never publicised and you never hear their authors on the radio.”

In the past 20 years, Novak has written half-a-dozen of these curios. Perhaps their authors are supremely wise. Writing books is not for most a profitable venture. “Most books only sell 500 copies, 1,000 copies,” says Andrew Crofts. “It’s only the odd one that takes off and becomes a phenomenon.” But even a single copy of a life offers a measure of immortality to its author. And who could put a price on that?

The Age of the Ghostwriter

Published on line at www.ojaiorange.com

The book sales charts are full of blockbusters by people who could obviously never write their own books. A sportsman at the top of his game? When’s he going to find the time to sit down and tap out eighty thousand words? A film star rushing from one movie set to the next? Paris Hilton? Sharon Osbourne? I don’t think so.

So who’s doing all the writing? Ghostwriters; professional scribes who live by the power of their pens and need a constant supply of new material. New material is just what the celebrities have, plus an audience of people ready and waiting to read what they have to say.

One of the leaders in the field in Andrew Crofts (his website, www.andrewcrofts.com, lists many of his titles, although he is more often anonymous). Based in Britain his books sell all over the world, often reaching number one in the sales charts. (At one time he had three in the charts simultaneously in the UK and several of his titles have been the best selling titles of their year in countries like England and France).

‘I was in an airport bookshop the other day,’ he says, ‘and was browsing through the book department. I found 12 different titles I had written on display in the biography section. Surprising, isn’t it?’

So why are so many books being ghosted?

‘It gives a book a lot more immediacy and power if it is written in the first person singular by the main protagonist. Imagine, for instance, a story about a young girl sold as a child bride in the Yemen; a book written about her by an objective author is never going to be as powerful as one describing the experience in her own words, seeing the world through her eyes.’

Crofts wrote a book called “Sold” on exactly that subject for a girl called Zana Muhsen, which has now sold around four million copies worldwide.

‘We wrote it over ten years ago,’ he says, ‘and I still receive e-mails every day from all over the globe, asking what has happened to Zana and her sister, Nadia, and telling me “Sold” is their favourite book of all time.’

Crofts has written through the eyes of a young Filipino girl who ended up murdering her English husband, a Pakistani slave boy, a Chinese billionaire, a Nigerian industrialist, several abused children, gangsters, courtesans, reality television stars and a host of other characters. Where else,’ he asks, ‘are you going to be able to meet and talk to such an interesting range of people? How else would you make the time to really find out about their lives and their thoughts? It’s a wonderful way to earn a living.’

Crofts thinks that it is possible as many as half the non-fiction books that find their way onto the shelves are written by ghosts.

‘And people should be very grateful that they are. Imagine how hard it would be to read books by all those non-professional writers. Just because you are a genius at football or a beautiful model does not mean that you are going to be able to tell your story in a readable way.’

Crofts usually spends just a few days talking with his subjects and then goes away for a couple of months to produce the manuscript, which they then get to check before anyone else sees it.

‘It’s crucial that they have complete trust in their ghost,’ he explains. ‘They must feel as confident about talking to them as they would to their doctor or lawyer. In fact a ghost is very like a lawyer, pleading his client’s case in court.’

So does Crofts miss seeing his name on the covers of his books?

‘Well, in fact, I’m finding that more and more publishers are including the ghosts in the credits. I think they are realising that the public doesn’t mind in the least, and would actually prefer not to be patronised. They have also found that the big retailers are more open to placing large advance orders if they recognise the name of the ghost on the project.’

It seems this truly is the age of the ghostwriter.